Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Moon - August 2012 Bead Journal Project

The moon is the primary night light of the skies, illuminating the land brightly on the nights of the full moon and receding again to the mystery of complete darkness at the new moon. This ancient enigma of constant regular appearance, growth, and subsequent disappearance is a visible symbol of life, death, and then rebirth with the appearance of the new moon. Ancient peoples measured time by the regular cycle of the moon rather than the cycle of the sun.

I choose to represent the moon for my August rune stone, part of my 2012 Bead Journal Project.

The focal point is an antique button, which had lost it's shank. I layered the button on a labradorite disk before bezeling the edges with seed beads in soft opalescent shades of grey, with just a touch of gold, to represent the reflected sun.

The edges and back of the stone show through the beaded netting I used to secure the focal to the stone.

As a mirror that reflects the light of the sun, the moon represents the shadow side of the sun’s light. The Moon can be said to reflect mystery and fear - it reminds us that we cannot see inside ourselves because we are unable to look directly at the brilliant sun. We look to the moon to see our face, just as we look into the mirror to see ourselves. The mirror of the moon illuminates both the darkness of the night, our shadow part, and the blue day sky, our conscious selves.

Many believe the moon is associated with clairvoyance and knowing without thinking. So to wear or have around you a symbol of the moon is to state your intention to use intuition, to simply go with what you feel in the moment.

Labels:

ART,

Bead Journal Project,

beads,

buttons,

Mackinac Island,

MackinArt,

mixed media,

moon

Saturday, August 25, 2012

Taking to the Waters: We Did It!!!

Well, our "Baseball & Bathing" weekend is over, just a fond memory now!

We started by gathering to watch a period baseball tournament, sponsored by Grand Hotel and enjoyed a fabulous picnic.

It's a great time for a period picnic, with so many fresh items available and appropriate. We had many great interactions with the modern spectators, who were quite intrigued by both our outfits and our lunch!

We strolled about town and then it was time for a bit of rest before our bathing excursion. It's about a two mile hike down to British Landing, and yes, we received more than a few stares as we made our way down to the water.

Here we are, in all our bathing glory (plus a couple non-bathers).

There had been a couple storms in the preceding week, which had unfortunately brought cold water to the surface - but it really wasn't too bad - or maybe we just became numb!

It was amazing how well all our ensembles came together - not that we don't all plan on a few "tweaks" now that they've actually been put to use.

Four of us submerged up to our shoulders, one decided the Lake Huron was just too cold and stayed on the shore

I suspect this may become an annual event for us - we had such a good time and hope we can convince a few more friends to join us in the future.

Our evening ended with a gorgeous sunset and another two mile hike, uphill this time, in our wet wool which was really not as unpleasant as it sounds.

I plan to post in depth details regarding the two bathing costumes I created - one male, one female, so more to come soon.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

Just a Little Blue

You probably have indigo dyed garments in your wardrobe - over one billion pairs of jeans around the world are dyed blue with indigo.

I recently participated in an indigo dyeing workshop and it was fascinating and fun!

Our instructor was Joann Condino, of Three Pines Studio and she was a fabulous teacher - I know I'm considering future projects.

Indigofera tinctoria was originally domesticated in India, where it is mentioned in manuscripts dating from the 4th century BC. It was recognised as a valuable blue dye by most early explorers of that region. The Venetian explorer Marco Polo described in detail the Indian indigo industry and by the 11th century, Arab traders had introduced indigo to the Mediterranean region, where it replaced their native blue dye plant, woad (Isatis tinctoria).

The cultivation of indigo on a large scale started in the 16th century in India and this was documented by European visitors in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in the north of India.

The British established commercial cultivation and production of indigo. Initial plantations began in 1777, and by 1788 most of the production of indigo purchased by the East India Company originated from Bengal. The system became deeply exploitative from 1837 when 'planters' were accorded permission to own land.

The East India Company imported massive volumes of Indian indigo in the mid 1600s. Its use in Europe was clearly a threat to native woad growers. Protests led to the ban of indigo in Britain and other European countries. Despite this, European woad plantations and factories rapidly disappeared.

Processing the plant was a cumbersome process:

The cut plant is tied into bundles, which are then packed into the fermenting vats and covered with clear fresh water. The vats, which are usually made of brick lined with cement, have an area of about 400 square feet and are 3 feet deep, are arranged in two rows, the tops of the bottom or "beating vats" being generally on a level with the bottoms of the fermenting vats. The indigo plant is allowed to steep till the rapid fermentation, which quickly sets in, has almost ceased, the time required being from 10-15 hours. The liquor, which varies from a pale straw colour to a golden-yellow, is then run into the beaters, where it is agitated either by men entering the vats and beating with oars, or by machinery. The colour of the liquid becomes green, then blue, and, finally, the indigo separates out as flakes, and is precipitated to the bottom of the vats. The indigo is allowed to thoroughly settle, when the supernatant liquid is drawn off. The pulpy mass of indigo is then boiled with water for some hours to remove impurities, filtered through thick woollen or coarse canvas bags, then pressed to remove as much of the moisture as possible, after which it is cut into cubes and finally air-dried.

But in 1865 the German chemist Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer began working with indigo.

His work culminated in the first synthesis of indigo in 1880 from o-nitrobenzaldehyde and acetone upon addition of dilute sodium hydroxide, barium hydroxide, or ammonia and the announcement of its chemical structure three years later.

BASF developed a commercially feasible manufacturing process that was in use by 1897, and by 1913 natural indigo had been almost entirely replaced by synthetic indigo. In 2002, 17,000 tons of synthetic indigo were produced worldwide.

Here's our dye vat, a five gallon bucket; you can see the "flower" floating on top, a result of oxygen reacting with the dye:

And it comes out green, not turning blue until the dye oxidizes when exposed to oxygen and reverts to its insoluble form.

That's my piece in the center of the clothesline:

And here's a much larger scale piece, created with rocks:

It was amazing how quickly and easily all of us were able to create beautiful and intricate patterns and, of course, I'm now contemplating how I can incorporate indigo into future projects, both for modern and living history purposes - more to come, I'm sure!

Indigofera tinctoria was originally domesticated in India, where it is mentioned in manuscripts dating from the 4th century BC. It was recognised as a valuable blue dye by most early explorers of that region. The Venetian explorer Marco Polo described in detail the Indian indigo industry and by the 11th century, Arab traders had introduced indigo to the Mediterranean region, where it replaced their native blue dye plant, woad (Isatis tinctoria).

The cultivation of indigo on a large scale started in the 16th century in India and this was documented by European visitors in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in the north of India.

The British established commercial cultivation and production of indigo. Initial plantations began in 1777, and by 1788 most of the production of indigo purchased by the East India Company originated from Bengal. The system became deeply exploitative from 1837 when 'planters' were accorded permission to own land.

The East India Company imported massive volumes of Indian indigo in the mid 1600s. Its use in Europe was clearly a threat to native woad growers. Protests led to the ban of indigo in Britain and other European countries. Despite this, European woad plantations and factories rapidly disappeared.

Processing the plant was a cumbersome process:

The cut plant is tied into bundles, which are then packed into the fermenting vats and covered with clear fresh water. The vats, which are usually made of brick lined with cement, have an area of about 400 square feet and are 3 feet deep, are arranged in two rows, the tops of the bottom or "beating vats" being generally on a level with the bottoms of the fermenting vats. The indigo plant is allowed to steep till the rapid fermentation, which quickly sets in, has almost ceased, the time required being from 10-15 hours. The liquor, which varies from a pale straw colour to a golden-yellow, is then run into the beaters, where it is agitated either by men entering the vats and beating with oars, or by machinery. The colour of the liquid becomes green, then blue, and, finally, the indigo separates out as flakes, and is precipitated to the bottom of the vats. The indigo is allowed to thoroughly settle, when the supernatant liquid is drawn off. The pulpy mass of indigo is then boiled with water for some hours to remove impurities, filtered through thick woollen or coarse canvas bags, then pressed to remove as much of the moisture as possible, after which it is cut into cubes and finally air-dried.

But in 1865 the German chemist Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer began working with indigo.

His work culminated in the first synthesis of indigo in 1880 from o-nitrobenzaldehyde and acetone upon addition of dilute sodium hydroxide, barium hydroxide, or ammonia and the announcement of its chemical structure three years later.

BASF developed a commercially feasible manufacturing process that was in use by 1897, and by 1913 natural indigo had been almost entirely replaced by synthetic indigo. In 2002, 17,000 tons of synthetic indigo were produced worldwide.

Dyeing with indigo is unique compared to other dyes. Natural indigo takes a considerable amount of effort to get it into a working dye bath because it is insoluble in water. It must go through a process where it is ‘reduced’ and put into a liquid state with the oxygen removed. Although recipes for dye vats vary, all are based on reducing the indigo into a watersoluble form.

However, Jacquard Products have come up with a clever way to make using natural indigo easy: Jacquard’s Indigo is pre-reduced by 60 % and easily mixes with water and therefore makes setting up an indigo vat practically effortless.

In class, we created resist patterns using a variety of methods - rubber bands, clothes pins, rocks, marbles, etc. on large squares of 100% cotton.

Here's our dye vat, a five gallon bucket; you can see the "flower" floating on top, a result of oxygen reacting with the dye:

The fabric needs to be wet when it goes in the vat

And it comes out green, not turning blue until the dye oxidizes when exposed to oxygen and reverts to its insoluble form.

That's my piece in the center of the clothesline:

And here's a much larger scale piece, created with rocks:

It was amazing how quickly and easily all of us were able to create beautiful and intricate patterns and, of course, I'm now contemplating how I can incorporate indigo into future projects, both for modern and living history purposes - more to come, I'm sure!

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

"Maple Sugar" - A Mixed Media Necklace

I've been revisiting a technique I've used in the past - mixed media pendents.

This photograph is my starting point:

It's Sugar Loaf, one of the many geological curiosities here on Mackinac Island. It stands 75' tall and in the fall is surrounded by a patchwork of bright maples and the greens of pine and cedar. The best view is from Point Lookout, which gives a panorama of the woods with the lake in the background.

I transferred the photo onto silk and then embellished the details with embroidery in silk and cotton and, of coarse, beads!

Available for purchase here.

Labels:

ART,

Backward Glances,

beads,

embroidery,

Mackinac Island,

MackinArt,

mixed media,

photography,

seed beads,

Sugar Loaf

Saturday, August 11, 2012

Tower Adventure

Yes, really!!!

We won a trip to the top of the Mackinac Bridge, a once in a lifetime opportunity.

After signing a waiver form and donning some oh-so-stylish Bridge Authority vests, our guide drove us to the south tower and opened the hatchway:

We then entered a very small elevator, maybe 2' x 3', which took us most of the way up the tower:

After that, we had to climb through a series of tiny hatchways and ladders, approximately 40' total:

And when we popped our heads through the final hatch, this was the view looking south, 552 feet above the water:

Looking north:

Looking towards home, Mackinac Island:

The cables are amazing:

One of the giant beacons on the top of the towers:

The towers don't allow a panoramic view to the east or the west:

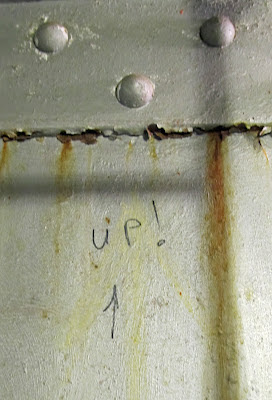

Then it was time to climb down again, here's a shot of the entry hatchway:

If you look closely, you'll see the note, "This way out" penciled above this hatchway - it's a bit of a maze inside the towers and it all looks alike, it would be really east to get all turned around!

Every Labor Day, thousand of people walk across the bridge - the only day that's allowed, but only a handful of people are ever able to ascend one of the towers. I've been in a boat under the bridge and drove over the bridge dozens of times, but I never thought I'd be at the top of the bridge - it was a true adventure!

Labels:

adventure,

Mackinac Bridge,

Straits of Mackinac,

tower

Sunday, August 5, 2012

In the Beginnings - An 1860's Fashion Show

Not too fashionable looking, am I?

Wash dress, apron, kerchief, and slat bonnet - basic garments that every female living historian should have and a great beginning to assembling a mid-19th century wardrobe.

Several years back, I was asked to present a fashion show at the annual Civil War event at Charlton Park, and I agreed - if I could do it my way.

So each show has a "theme" and this year I decided to address a question I frequently hear from spectators - no, not "Are you hot in those clothes?" - but "How do you put together a wardrobe?"

We started by showing the underpinnings, chemise, corset, drawers, petticoats, etc and explained WHY it's so important to have those layers before moving on to a dress - without the proper foundation, it's impossible to have the proper silhouette for the period.

We also discussed why under garments are the perfect place for a novice seamstress to practice - the skills used can all be used in outer garments, and after all, if they aren't absolutely perfect, they won't be visible to the general public.

Skirt support was our next topic and also provided an opportunity to discuss research and trends in reenacting - we are both wearing corded petticoats, which for several years were the "in" thing, but further research has shown that by the war years, they were a bit of a rarity, having been replaced by the ubiquitous cage crinoline.

We also talked about the life cycle of garments - here we have what was previously a more fashionable dress, but it's become a bit faded and shabby and has now been relegated to work wear - think about the jeans that you now only wear when cleaning house. Clothing should be appropriate for the task at hand, why wear a fancy gown for messy tasks?

Another use for a dress past it's prime is to use it for yardage: just think how many aprons, slat bonnets, or children's garments a skirt could yield.

Removing that slat bonnet, apron and adding a plain white collar sure changed the look of my very basic dress!

Another versatile garment is a wrapper - great for early morning runs to the necessary without needing to get fully dressed and, due to the relatively loose fit, a very forgiving garment for the beginning seamstress. In this case, with permission, I shared the mistake made by the maker and her creative and appropriate solution - she had made her wrapper too short, but instead of discarding it, she added more fabric, running in the opposite direction to add length - it's a great solution, adds interest to the garment and looks intentional.

Here's another reason to start with a simple wash dress - you'll learn the skills to create a more fashionable gown. If you look closely, our basic dresses are very similar: fitted, gathered bodices and simple bishop sleeves. The difference is the finer fabric and bold trim of the dress on the left, as well as the stylish straw bonnet.

Here's another lovely example: striped sheer silk, with slim open sleeves worn over lace trimmed undersleeves, with a larger skirt support and accessorized with bonnet, gloves and reticule - she's ready to pay a call on friends!

Again, the biggest differences between my wash dress and this gown suitable for visiting, are the fabrics and accessories - the rest is just details.

Despite having only a handful of models, I was able to share a huge amount of information with the viewers and they stayed to listen, standing in the sun on a 95 degree hot and humid day!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)